#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# ### Data Exploration of a publicly available dataset.

#

#  #

# Data processing, cleaning and normalization is often 95% of the battle. Never underestimate this part of the process, if you're not careful about it your derrière will be sore later. Another good reason to spend a bit of time on understanding your data is that you may realize that the data isn't going to be useful for your task at hand. Quick pruning of fruitless branches is good.

#

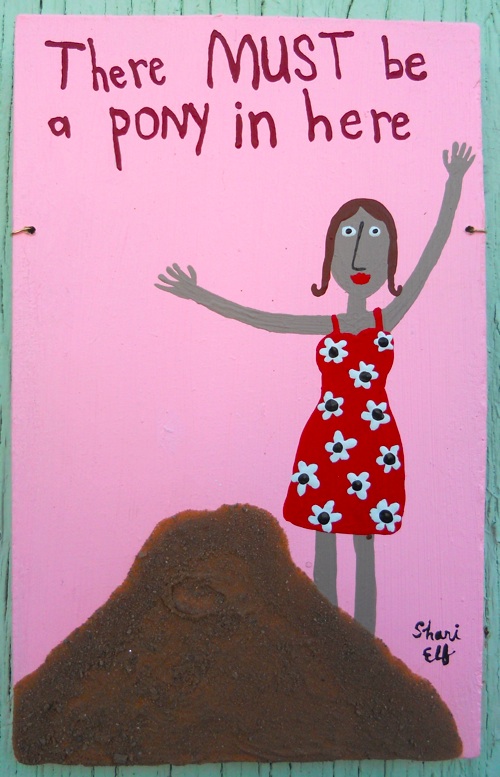

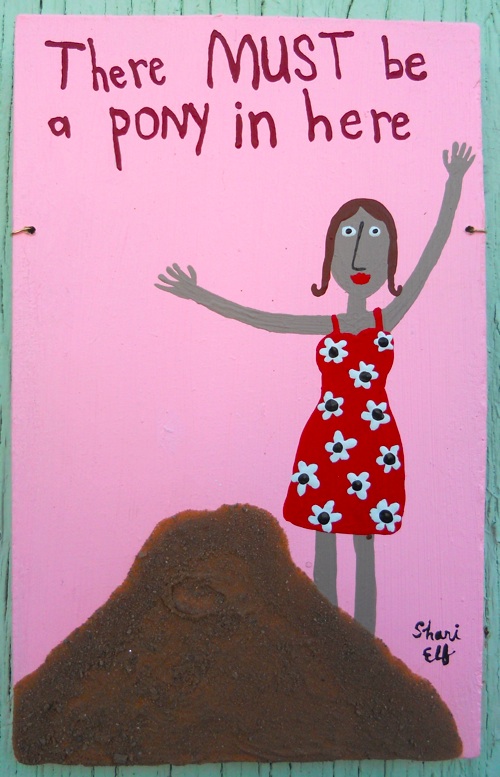

# #### Data as an analogy: Data is almost always a big pile of shit, the only real question is, "Is there a Pony inside?" and that's what data exploration and understanding is about. ####

#

# For this exploration we're going to pull some data from the Malware Domain List website [http://www.malwaredomainlist.com](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com). We'd like to thank them for providing a great resourse and making their data available to the public. In general data is messy so even though we're going to be nit-picking quite a bit, we recognized that many datasets will have similar issues which is why we feel like this is a good 'real world' example of data.

#

# * Full database: [ http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php)

# In[1]:

# This exercise is mostly for us to understand what kind of data we have and then

# run some simple stats on the fields/values in the data. Pandas will be great for that

import pandas as pd

pd.__version__

# In[2]:

# Set default figure sizes

pylab.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (14.0, 5.0)

# In[3]:

# This data url can be a web location http://foo.bar.com/mydata.csv or it can be a

# a path to your disk where the data resides /full/path/to/data/mydata.csv

# Note: Be a good web citizen, download the data once and then specify a path to your local file :)

# For instance: > wget http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php -O mdl_data.csv

# data_url = 'http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php'

data_url = 'data/mdl_data.csv'

# In[4]:

# Note: when the data was pulled it didn't have column names, so poking around

# on the website we found the column headers referenced so we're explicitly

# specifying them to the CSV reader:

# date,domain,ip,reverse,description,registrant,asn,inactive,country

dataframe = pd.read_csv(data_url, names=['date','domain','ip','reverse','description',

'registrant','asn','inactive','country'], header=None, error_bad_lines=False, low_memory=False)

# In[5]:

dataframe.head(5)

# In[6]:

dataframe.tail(5)

# In[7]:

# We can see there's a blank row at the end that got filled with NaNs

# Thankfully Pandas is great about handling missing data.

print dataframe.shape

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[8]:

# For this use case we're going to remove any rows that have a '-' in the data

# by replacing '-' with NaN and then running dropna() again

dataframe = dataframe.replace('-', np.nan)

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[9]:

# Drilling down into one of the columns

dataframe['description']

# In[10]:

# Pandas has a describe method

# For numerical data it give a nice set of summary statistics

# For categorical data it simply gives count, unique values

# and the most common value

dataframe['description'].describe()

# In[11]:

# We can get a count of all the unique values by running value_counts()

dataframe['description'].value_counts()

# In[12]:

# We noticed that the description values just differ by whitespace or captilization

dataframe['description'] = dataframe['description'].map(lambda x: x.strip().lower())

dataframe['description']

# In[13]:

# First thing we noticed was that many of the 'submissions' had the exact same

# date, which we're guessing means some batch jobs just through a bunch of

# domains in and stamped them all with the same date.

# We also noticed that many values just differ by captilization (this is common)

dataframe = dataframe.applymap(lambda x: x.strip().lower() if not isinstance(x,float64) else x)

dataframe.head()

# In[14]:

# The domain column looks to be full URI instead of just the domain

from urlparse import urlparse

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].astype(str)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: "http://" + x)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: urlparse(x).netloc)

# ### Two columns that are a mistaken copy of each other?...

# We also suspect that the 'inactive' column and the 'country' column are exactly the same, also why is there one row in the inactive column with a value of '2'?

#

#

# Data processing, cleaning and normalization is often 95% of the battle. Never underestimate this part of the process, if you're not careful about it your derrière will be sore later. Another good reason to spend a bit of time on understanding your data is that you may realize that the data isn't going to be useful for your task at hand. Quick pruning of fruitless branches is good.

#

# #### Data as an analogy: Data is almost always a big pile of shit, the only real question is, "Is there a Pony inside?" and that's what data exploration and understanding is about. ####

#

# For this exploration we're going to pull some data from the Malware Domain List website [http://www.malwaredomainlist.com](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com). We'd like to thank them for providing a great resourse and making their data available to the public. In general data is messy so even though we're going to be nit-picking quite a bit, we recognized that many datasets will have similar issues which is why we feel like this is a good 'real world' example of data.

#

# * Full database: [ http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php)

# In[1]:

# This exercise is mostly for us to understand what kind of data we have and then

# run some simple stats on the fields/values in the data. Pandas will be great for that

import pandas as pd

pd.__version__

# In[2]:

# Set default figure sizes

pylab.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (14.0, 5.0)

# In[3]:

# This data url can be a web location http://foo.bar.com/mydata.csv or it can be a

# a path to your disk where the data resides /full/path/to/data/mydata.csv

# Note: Be a good web citizen, download the data once and then specify a path to your local file :)

# For instance: > wget http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php -O mdl_data.csv

# data_url = 'http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php'

data_url = 'data/mdl_data.csv'

# In[4]:

# Note: when the data was pulled it didn't have column names, so poking around

# on the website we found the column headers referenced so we're explicitly

# specifying them to the CSV reader:

# date,domain,ip,reverse,description,registrant,asn,inactive,country

dataframe = pd.read_csv(data_url, names=['date','domain','ip','reverse','description',

'registrant','asn','inactive','country'], header=None, error_bad_lines=False, low_memory=False)

# In[5]:

dataframe.head(5)

# In[6]:

dataframe.tail(5)

# In[7]:

# We can see there's a blank row at the end that got filled with NaNs

# Thankfully Pandas is great about handling missing data.

print dataframe.shape

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[8]:

# For this use case we're going to remove any rows that have a '-' in the data

# by replacing '-' with NaN and then running dropna() again

dataframe = dataframe.replace('-', np.nan)

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[9]:

# Drilling down into one of the columns

dataframe['description']

# In[10]:

# Pandas has a describe method

# For numerical data it give a nice set of summary statistics

# For categorical data it simply gives count, unique values

# and the most common value

dataframe['description'].describe()

# In[11]:

# We can get a count of all the unique values by running value_counts()

dataframe['description'].value_counts()

# In[12]:

# We noticed that the description values just differ by whitespace or captilization

dataframe['description'] = dataframe['description'].map(lambda x: x.strip().lower())

dataframe['description']

# In[13]:

# First thing we noticed was that many of the 'submissions' had the exact same

# date, which we're guessing means some batch jobs just through a bunch of

# domains in and stamped them all with the same date.

# We also noticed that many values just differ by captilization (this is common)

dataframe = dataframe.applymap(lambda x: x.strip().lower() if not isinstance(x,float64) else x)

dataframe.head()

# In[14]:

# The domain column looks to be full URI instead of just the domain

from urlparse import urlparse

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].astype(str)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: "http://" + x)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: urlparse(x).netloc)

# ### Two columns that are a mistaken copy of each other?...

# We also suspect that the 'inactive' column and the 'country' column are exactly the same, also why is there one row in the inactive column with a value of '2'?

#

# "Ahhh, what an awful dream. Ones and zeroes everywhere... and I thought I saw a two [shudder]."

# -- Bender

# "It was just a dream, Bender. There's no such thing as two".

# -- Fry

#

# In[15]:

# Using numpy.corrcoef to compute the correlation coefficient matrix

np.corrcoef(dataframe["inactive"], dataframe["country"])

# In[16]:

# Pandas also has a correlation method on it's dataframe which has nicer output

dataframe.corr()

# In[17]:

# Yeah perfectly correlated, so looks like 'country'

# is just the 'inactive' column duplicated.

# So what happened here? Seems bizarre to have a replicated column.

# #### Okay well lets try to get something out of this pile. We'd like to run some simple statistics to see what correlations the data might contain.

#

# #### G-test is for goodness of fit to a distribution and for independence in contingency tables. It's related to chi-squared, multinomial and Fisher's exact test, please see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G_test.

#

# In[18]:

# The data hacking repository has a simple stats module we're going to use

import data_hacking.simple_stats as ss

# Spin up our g_test class

g_test = ss.GTest()

# Here we'd like to see how various exploits (description) are related to

# the ASN (Autonomous System Number) associated with the ip/domain.

(exploits, matches, cont_table) = g_test.highest_gtest_scores(

dataframe['description'], dataframe['asn'], N=5, matches=5)

ax = exploits.T.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True)

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('ASN (Autonomous System Number)')

patches, labels = ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

ax.legend(patches, labels, loc='upper right')

# The plot below is showing the number of times a particular exploit was associated with an ASN.

# Interesing to see whether exploits are highly correlated to particular ASNs.

# In[19]:

# Now we use g_test with the 'reverse=True' argument to display those exploits

# that do not have a high correlation with a particular ASN.

exploits, matches, cont_table = g_test.highest_gtest_scores(dataframe['description'],

dataframe['asn'], N=7, reverse=True, min_volume=500, matches=15)

ax = exploits.T.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True)

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('ASN (Autonomous System Number)')

patches, labels = ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

ax.legend(patches, labels, loc='best')

# The plot below is showing exploits who aren't associated with any particular ASN.

# Interesing to see exploits that are spanning many ASNs.

# In[20]:

exploits, matches, cont_table = g_test.highest_gtest_scores(dataframe['description'],

dataframe['domain'], N=5)

ax = exploits.T.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True) #, log=True)

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('Domain')

patches, labels = ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

ax.legend(patches, labels, loc='best')

# The Contingency Table below is just showing the counts of the number of times

# a particular exploit was associated with an TLD.

# In[21]:

# Drilling down on one particular exploit

banker = dataframe[dataframe['description']=='trojan banker'] # Subset dataframe

exploits, matches, cont_table = g_test.highest_gtest_scores(banker['description'], banker['domain'], N=5)

import pprint

pprint.pprint(["Domain: %s Count: %d" % (domain,count) for domain,count in exploits.iloc[0].iteritems()])

# ### So switching gears, perhaps we'll look at date range, volume over time, etc.

#

# Pandas also has reasonably good functionality for date/range processing and plotting.

# In[22]:

# Add the proper timestamps to the dataframe replacing the old ones

dataframe['date'] = dataframe['date'].apply(lambda x: str(x).replace('_','T'))

dataframe['date'] = pd.to_datetime(dataframe['date'])

# In[23]:

# Now prepare the data for plotting by pivoting on the

# description to create a new column (series) for each value

# We're going to add a new column called value (needed for pivot). This

# is a bit dorky, but needed as the new columns that get created should

# really have a value in them, also we can use this as our value to sum over.

subset = dataframe[['date','description']]

subset['count'] = 1

pivot = pd.pivot_table(subset, values='count', rows=['date'], cols=['description'], fill_value=0)

by = lambda x: lambda y: getattr(y, x)

grouped = pivot.groupby([by('year'),by('month')]).sum()

# Only pull out the top 7 desciptions (exploit types)

topN = subset['description'].value_counts()[:7].index

grouped[topN].plot()

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('Date Submitted')

# The plot below shows the volume of particular exploits impacting new domains.

# Tracking the ebb and flow of exploits over time might be useful

# depending on the type of analysis you're doing.

# In[24]:

# The rise and fall of the different exploits is intriguing but

# the taper at the end is concerning, let look at total volume of

# new malicious domains coming into the MDL database.

total_mdl = dataframe['description']

total_mdl.index=dataframe['date']

total_agg = total_mdl.groupby([by('year'),by('month')]).count()

matplotlib.pyplot.figure()

total_agg.plot(label='New Domains in MDL Database')

pylab.ylabel('Total Exploits')

pylab.xlabel('Date Submitted')

matplotlib.pyplot.legend()

# ### That doesn't look good...

# The plot above shows the total volume of ALL newly submitted domains. We see from the plot that the taper is a general overall effect due to a drop in new domain submissions into the MDL database. Given the recent anemic volume there might be another data source that has more active submissions.

#

# Well the anemic volume issue aside we're going to carry on by looking at the correlations in volume over time. In other words are the volume of reported exploits closely related to the volume of other exploits...

#

# ### Correlations of Volume Over Time

#

# - **Prof. Farnsworth:** Behold! The Deathclock!

#

- **Leela:** Does it really work?

#

- **Prof. Farnsworth:** Well, it's occasionally off by a few seconds, what with "free will" and all.

#

# In[25]:

# Only pull out the top 20 desciptions (exploit types)

topN = subset['description'].value_counts()[:20].index

corr_df = grouped[topN].corr()

# In[26]:

# Statsmodels has a correlation plot, we expect the diagonal to have perfect

# correlation (1.0) but anything high score off the diagonal means that

# the volume of different exploits are temporally correlated.

import statsmodels.api as sm

corr_df.sort(axis=0, inplace=True) # Just sorting so exploits names are easy to find

corr_df.sort(axis=1, inplace=True)

corr_matrix = corr_df.as_matrix()

pylab.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (8.0, 8.0)

sm.graphics.plot_corr(corr_matrix, xnames=corr_df.index.tolist())

plt.show()

# #### Discussion of Correlation Matrix

# * The two sets of 3x3 red blocks on the lower right make intuitive sense, Zeus config file, drop zone and trojan show almost perfect volume over time correlation.

# In[27]:

pylab.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (14.0, 3.0)

print grouped[['zeus v1 trojan','zeus v1 config file','zeus v1 drop zone']].corr()

grouped[['zeus v1 trojan','zeus v1 config file','zeus v1 drop zone']].plot()

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('Date Submitted')

# In[28]:

grouped[['zeus v2 trojan','zeus v2 config file','zeus v2 drop zone']].plot()

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('Date Submitted')

# In[29]:

# Drilling down on the correlation between 'trojan' and 'phoenix exploit kit'

print grouped[['trojan','phoenix exploit kit']].corr()

grouped[['trojan','phoenix exploit kit']].plot()

pylab.ylabel('Exploit Occurrences')

pylab.xlabel('Date Submitted')

# ### Interesting? (shrug... maybe...)

# Looking above we see that the generic 'trojan' label and the fairly specific 'phoenix exploit kit' have a reasonable volume over time correlation of .834 *(PearsonsR is the default for the corr() function; a score of 1.0 means perfectly correlated [Pearson's Correlation](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearson_product-moment_correlation_coefficient))*. So it certainly might be something to dive into depending on your particular interest, again the win here is that with a few lines of python code we can 'see' these kinds of relationships.

# ### Conclusions

# So this exercise was an exploration of the dataset. At this point we have a good idea about what's in the dataset, what cleanup issues we might have and the overall quality of the dataset. We've run some simple correlative statistics and produced some nice plots. Most importantly we should have a good feel for whether this dataset is going to suite our needs for whatever use case we may have.

#

# In the next exercise we're going look at some syslog data. We'll take it up a notch by computing similarities with 'Banded MinHash', running a heirarchical clustering algorithm and exercising some popular supervised machine learning functionality from Scikit Learn http://scikit-learn.org/.

#

# Data processing, cleaning and normalization is often 95% of the battle. Never underestimate this part of the process, if you're not careful about it your derrière will be sore later. Another good reason to spend a bit of time on understanding your data is that you may realize that the data isn't going to be useful for your task at hand. Quick pruning of fruitless branches is good.

#

# #### Data as an analogy: Data is almost always a big pile of shit, the only real question is, "Is there a Pony inside?" and that's what data exploration and understanding is about. ####

#

# For this exploration we're going to pull some data from the Malware Domain List website [http://www.malwaredomainlist.com](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com). We'd like to thank them for providing a great resourse and making their data available to the public. In general data is messy so even though we're going to be nit-picking quite a bit, we recognized that many datasets will have similar issues which is why we feel like this is a good 'real world' example of data.

#

# * Full database: [ http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php)

# In[1]:

# This exercise is mostly for us to understand what kind of data we have and then

# run some simple stats on the fields/values in the data. Pandas will be great for that

import pandas as pd

pd.__version__

# In[2]:

# Set default figure sizes

pylab.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (14.0, 5.0)

# In[3]:

# This data url can be a web location http://foo.bar.com/mydata.csv or it can be a

# a path to your disk where the data resides /full/path/to/data/mydata.csv

# Note: Be a good web citizen, download the data once and then specify a path to your local file :)

# For instance: > wget http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php -O mdl_data.csv

# data_url = 'http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php'

data_url = 'data/mdl_data.csv'

# In[4]:

# Note: when the data was pulled it didn't have column names, so poking around

# on the website we found the column headers referenced so we're explicitly

# specifying them to the CSV reader:

# date,domain,ip,reverse,description,registrant,asn,inactive,country

dataframe = pd.read_csv(data_url, names=['date','domain','ip','reverse','description',

'registrant','asn','inactive','country'], header=None, error_bad_lines=False, low_memory=False)

# In[5]:

dataframe.head(5)

# In[6]:

dataframe.tail(5)

# In[7]:

# We can see there's a blank row at the end that got filled with NaNs

# Thankfully Pandas is great about handling missing data.

print dataframe.shape

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[8]:

# For this use case we're going to remove any rows that have a '-' in the data

# by replacing '-' with NaN and then running dropna() again

dataframe = dataframe.replace('-', np.nan)

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[9]:

# Drilling down into one of the columns

dataframe['description']

# In[10]:

# Pandas has a describe method

# For numerical data it give a nice set of summary statistics

# For categorical data it simply gives count, unique values

# and the most common value

dataframe['description'].describe()

# In[11]:

# We can get a count of all the unique values by running value_counts()

dataframe['description'].value_counts()

# In[12]:

# We noticed that the description values just differ by whitespace or captilization

dataframe['description'] = dataframe['description'].map(lambda x: x.strip().lower())

dataframe['description']

# In[13]:

# First thing we noticed was that many of the 'submissions' had the exact same

# date, which we're guessing means some batch jobs just through a bunch of

# domains in and stamped them all with the same date.

# We also noticed that many values just differ by captilization (this is common)

dataframe = dataframe.applymap(lambda x: x.strip().lower() if not isinstance(x,float64) else x)

dataframe.head()

# In[14]:

# The domain column looks to be full URI instead of just the domain

from urlparse import urlparse

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].astype(str)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: "http://" + x)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: urlparse(x).netloc)

# ### Two columns that are a mistaken copy of each other?...

# We also suspect that the 'inactive' column and the 'country' column are exactly the same, also why is there one row in the inactive column with a value of '2'?

#

#

# Data processing, cleaning and normalization is often 95% of the battle. Never underestimate this part of the process, if you're not careful about it your derrière will be sore later. Another good reason to spend a bit of time on understanding your data is that you may realize that the data isn't going to be useful for your task at hand. Quick pruning of fruitless branches is good.

#

# #### Data as an analogy: Data is almost always a big pile of shit, the only real question is, "Is there a Pony inside?" and that's what data exploration and understanding is about. ####

#

# For this exploration we're going to pull some data from the Malware Domain List website [http://www.malwaredomainlist.com](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com). We'd like to thank them for providing a great resourse and making their data available to the public. In general data is messy so even though we're going to be nit-picking quite a bit, we recognized that many datasets will have similar issues which is why we feel like this is a good 'real world' example of data.

#

# * Full database: [ http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php](http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php)

# In[1]:

# This exercise is mostly for us to understand what kind of data we have and then

# run some simple stats on the fields/values in the data. Pandas will be great for that

import pandas as pd

pd.__version__

# In[2]:

# Set default figure sizes

pylab.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (14.0, 5.0)

# In[3]:

# This data url can be a web location http://foo.bar.com/mydata.csv or it can be a

# a path to your disk where the data resides /full/path/to/data/mydata.csv

# Note: Be a good web citizen, download the data once and then specify a path to your local file :)

# For instance: > wget http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php -O mdl_data.csv

# data_url = 'http://www.malwaredomainlist.com/mdlcsv.php'

data_url = 'data/mdl_data.csv'

# In[4]:

# Note: when the data was pulled it didn't have column names, so poking around

# on the website we found the column headers referenced so we're explicitly

# specifying them to the CSV reader:

# date,domain,ip,reverse,description,registrant,asn,inactive,country

dataframe = pd.read_csv(data_url, names=['date','domain','ip','reverse','description',

'registrant','asn','inactive','country'], header=None, error_bad_lines=False, low_memory=False)

# In[5]:

dataframe.head(5)

# In[6]:

dataframe.tail(5)

# In[7]:

# We can see there's a blank row at the end that got filled with NaNs

# Thankfully Pandas is great about handling missing data.

print dataframe.shape

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[8]:

# For this use case we're going to remove any rows that have a '-' in the data

# by replacing '-' with NaN and then running dropna() again

dataframe = dataframe.replace('-', np.nan)

dataframe = dataframe.dropna()

dataframe.shape

# In[9]:

# Drilling down into one of the columns

dataframe['description']

# In[10]:

# Pandas has a describe method

# For numerical data it give a nice set of summary statistics

# For categorical data it simply gives count, unique values

# and the most common value

dataframe['description'].describe()

# In[11]:

# We can get a count of all the unique values by running value_counts()

dataframe['description'].value_counts()

# In[12]:

# We noticed that the description values just differ by whitespace or captilization

dataframe['description'] = dataframe['description'].map(lambda x: x.strip().lower())

dataframe['description']

# In[13]:

# First thing we noticed was that many of the 'submissions' had the exact same

# date, which we're guessing means some batch jobs just through a bunch of

# domains in and stamped them all with the same date.

# We also noticed that many values just differ by captilization (this is common)

dataframe = dataframe.applymap(lambda x: x.strip().lower() if not isinstance(x,float64) else x)

dataframe.head()

# In[14]:

# The domain column looks to be full URI instead of just the domain

from urlparse import urlparse

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].astype(str)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: "http://" + x)

dataframe['domain'] = dataframe['domain'].apply(lambda x: urlparse(x).netloc)

# ### Two columns that are a mistaken copy of each other?...

# We also suspect that the 'inactive' column and the 'country' column are exactly the same, also why is there one row in the inactive column with a value of '2'?

#